The Holy Blood of Bruges-la-Morte

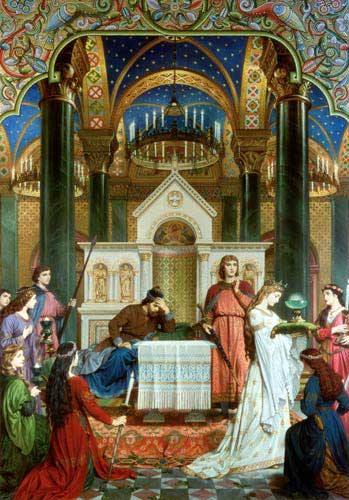

The epic poem Perceval, Le Conte du Graal launched the Holy Grail into Western literature. Written by French poet Chrétien de Troyes in the 1180s, the storyline introduces a certain Perceval to us, who is invited to stay in the castle of the Fisher King where he witnesses a mysterious procession. With each course of the meal, young men and women pass before him with magnificent objects: a bleeding lance, candelabras and a beautiful girl with what is described as an elaborately decorated Graal. This object contains a single Mass wafer for the Fisher King to sustain his wounds. As it turns out, the Fisher King is a cousin of Perceval. When the young man wakes up the next morning, he finds himself alone in the woods and the castle disappeared. Later on, he learns that he should have made an inquiry into this Graal as the right question would have healed the Fisher King. He vows to find the Castle of the Grail again one day but it remains unclear from the poem if he ever does.

The epic poem Perceval, Le Conte du Graal launched the Holy Grail into Western literature. Written by French poet Chrétien de Troyes in the 1180s, the storyline introduces a certain Perceval to us, who is invited to stay in the castle of the Fisher King where he witnesses a mysterious procession. With each course of the meal, young men and women pass before him with magnificent objects: a bleeding lance, candelabras and a beautiful girl with what is described as an elaborately decorated Graal. This object contains a single Mass wafer for the Fisher King to sustain his wounds. As it turns out, the Fisher King is a cousin of Perceval. When the young man wakes up the next morning, he finds himself alone in the woods and the castle disappeared. Later on, he learns that he should have made an inquiry into this Graal as the right question would have healed the Fisher King. He vows to find the Castle of the Grail again one day but it remains unclear from the poem if he ever does.

You mean a Grail….?

Chrétien keeps us in the dark as to what exactly this Grail is. To some it is exactly that which is the appeal of his story: the mystery surrounding the object and the uncertainty of its whereabouts. Some scholars claim the Grail was distilled from Celtic mythology. They recognize a cauldron with the power to restore people or to even raise the dead. They see a Vessel of Plenty, a Magical Platter symbolizing otherworldly powers and sometimes even the power to select Kings.

Most scholars claim that in Perceval the Grail hadn’t yet acquired the holiness it displays in later Grail romances. I don’t agree. Chrétien’s Grail wasn’t a dish or bowl containing a salmon or a mere pike but a single Mass wafer. The mystical fasting of the crippled Fisher King reminds us of the countless saints who were said to have lived on a wafer a day. Chrétien definitely intended the Mass wafer to be a significant part of the ritual. Maybe, being the first modern European novelist, he would have unveiled the true identity and the Secret of the Grail at the end of his story. Unfortunately death overtook him, leaving the poem unfinished.

Around the period the first Grail romances were written, the Church of Rome was beginning to add more mysticism to the Sacrament of the Holy Communion. In that respect, the Grail could have been a purely Christian symbol from the very beginning. Twelfth century wall paintings present images of the Virgin holding a bowl radiating tongues of fire. They might well have been the original inspiration for the Grail legend.

Around the period the first Grail romances were written, the Church of Rome was beginning to add more mysticism to the Sacrament of the Holy Communion. In that respect, the Grail could have been a purely Christian symbol from the very beginning. Twelfth century wall paintings present images of the Virgin holding a bowl radiating tongues of fire. They might well have been the original inspiration for the Grail legend.

The word ‘Grail’ seems to be an Old French adaptation of the Latin ‘gradalis’, simply meaning: a dish. later Medieval writers claimed the word to actually being ‘sangréal’ ‘“ French for ‘royal blood’ ‘“ which became ‘san graal’, Saint Grail… or Holy Blood. This is called ‘a false etymology’, but I am not convinced it is that false. French and English authors tend to forget that Chrétien states very clearly that he was working from a source book given to him by Philip of Alsace, son of Thierry…the man who brought a relic holding the Holy Blood from Jerusalem to Bruges.

Enter’¦ the Templars

The Order of the Knights Templar was founded around 1119 by Hugues de Payens, a French noble man from the Champagne. For his order he chose eight knights, the most important of them being Godfrey de Saint-Omer. According to legend, Hugues and Godfrey were so poor that they had only one horse, so the famous image on the Temple seal became that of two men riding a single horse. Godfrey is often portrayed as a French knight because Saint-Omer belongs to modern France. At the time however it was part of Flanders and Godfrey was a vassal to its Count Robert II.

The mission of the Templars was to protect the pilgrims who visited the Holy Land, but for nine years little was heard of the them at all. From 1129 onwards however, after the Council of Troyes had officially sanctioned the Order, the Templars gradually became a known and recognized force throughout Europe. The rule of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Solomonici in Latin, or shortly: Milites Christi, Soldiers of Christ) was kept in the Abbey of the Dunes in Coxyde, not far from Bruges and Saint-Omer. The rule was written by St. Bernard of Clairvaux. The Templars had to be warrior-monks, soldier-mystics, ‘a militia of Christ’. The first headquarters of the Temple in Europe, was in Ypres ‘“ near Bruges and Saint-Omer again. In fact, the property had been a gift from Godfrey de Saint-Omer to the order.

The mission of the Templars was to protect the pilgrims who visited the Holy Land, but for nine years little was heard of the them at all. From 1129 onwards however, after the Council of Troyes had officially sanctioned the Order, the Templars gradually became a known and recognized force throughout Europe. The rule of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Solomonici in Latin, or shortly: Milites Christi, Soldiers of Christ) was kept in the Abbey of the Dunes in Coxyde, not far from Bruges and Saint-Omer. The rule was written by St. Bernard of Clairvaux. The Templars had to be warrior-monks, soldier-mystics, ‘a militia of Christ’. The first headquarters of the Temple in Europe, was in Ypres ‘“ near Bruges and Saint-Omer again. In fact, the property had been a gift from Godfrey de Saint-Omer to the order.

The history of the Temple was primarily recorded by French and English authors, from their French and English perspectives. They often forget to mention ‘“ or don’t know ‘“ that the Templars always had a very strong ‘Flemish Connection’. One of the most (in)famous Grand Masters of the Order was Gerard de Ridefort, who definitely had Flemish roots, even though 19th century writers suggested an Anglo-Norman background. In the Flemish village of Ruddervoorde (‘Ridefort’) there still are many legends surrounding the Temple Commandery he once ruled.

Bestseller authors like Lincoln, Baigent & Leigh (Holy Blood, Holy Grail) and Dan Brown (The Da Vinci Code) claim that the Templars discovered ‘something’ in the ruins of the Temple. Hypotheses about that “something” range from the Ark of the Covenant to documents, artefacts or relics proving Jesus survived the Crucifixion or was married to Mary Magdalene. One story claims they found the Holy Grail, which got transported to Scotland in 1307 to be buried beneath Rosslyn Chapel. In actual fact there is not one single piece of documentary evidence for any story in which the “something” is brought from the Holy Land to Europe by the Knights Templar. Any with one exception that is: the Holy Blood of Bruges.

From the 1970s Belgian scholars like Paul de Saint Hilaire (La Belgique Mystérieuse, La Flandre Mystérieuse, L’Ardenne Mystérieuse) and Hubert Lampo (De Zwanen van Stonehenge/The Swans of Stonehenge) have been writing articles and books about the one and only Holy Blood (or Holy Grail) of Bruges.

Bruges or the New Jerusalem

Around the same the time that the Order of the Knights Templar was founded, Thierry of Alsace claimed the county of Flanders against William Clito. Thierry was supported by the mighty cities of Bruges, Ghent, Lille and Saint-Omer. He won the battle and in 1128 set up his government in Ghent. In 1139 he married Sybilla of Anjou, daughter of the King of Jerusalem. She was pregnant when Thierry left Flanders for the Second Crusade and got attacked in his absence by Baldwin IV of Hainaut. In an early display of girlpower, the brave Princess launched a counter-attack and pillaged Baldwin’s county by means of reply. In synch with his wife, Thierry participated in the Siege of Damascus, led by his wife’s half-brother Baldwin III, King of Jerusalem. War was truly a family affair in these days.

A legend says that on Christmas Day 1148, some Templars found a stone jar in the Holy Grave. Thierry and Sybilla are claimed to have been present which is impossible because we know she was chasing Baldwin of Hainaut at the time, an enormous journey away from Jerusalem. According to the legend, the Templar were convinced the jar contained the Holy Blood of Christ. The Holy Blood was respectfully poured from the jar into an octogonal bottle and the ends were sealed with two golden roses. Now Sybilla of Anjou was a leper who suffered from terrible attacks of fever. After the sealing of the bottle, she held the precious Relic in her hands for just a moment, triggering in her a vision of ‘a New Jerusalem of the West’: the city of Bruges. In the same moment Sybilla and all lepers surrounding here had been miraculously cured.

A legend says that on Christmas Day 1148, some Templars found a stone jar in the Holy Grave. Thierry and Sybilla are claimed to have been present which is impossible because we know she was chasing Baldwin of Hainaut at the time, an enormous journey away from Jerusalem. According to the legend, the Templar were convinced the jar contained the Holy Blood of Christ. The Holy Blood was respectfully poured from the jar into an octogonal bottle and the ends were sealed with two golden roses. Now Sybilla of Anjou was a leper who suffered from terrible attacks of fever. After the sealing of the bottle, she held the precious Relic in her hands for just a moment, triggering in her a vision of ‘a New Jerusalem of the West’: the city of Bruges. In the same moment Sybilla and all lepers surrounding here had been miraculously cured.

Sybilla made a solemn pledge to turn Bruges into a Holy City. In 1150 Sybilla, her husband Thierry, the abbot of Saint Bertin and the Flemish crusaders arrived in Bruges, where masons had just finished the basilica of Saint-Basilius on the Burg Square. The Holy Blood is kept there to this day and has been called upon for an enormous variety of reasons.

Sybilla made a solemn pledge to turn Bruges into a Holy City. In 1150 Sybilla, her husband Thierry, the abbot of Saint Bertin and the Flemish crusaders arrived in Bruges, where masons had just finished the basilica of Saint-Basilius on the Burg Square. The Holy Blood is kept there to this day and has been called upon for an enormous variety of reasons.

The oldest document concerning this Sanguis Christi or Blood of Christ dates from 1256. The legend is very precise about a much earlier date, namely April 7, 1150. Whether or not the relic really holds the Blood of the Saviour can never be established for fact. What is certain is that the Templars who gave the Relic to the Count of Flanders believed it and wanted it to be.

When Thierry left for the Holy Land for the third time Sybilla came with him. On her arrival in Jerusalem, she separated from Thierry and joined the Convent of St. Lazarus in Bethany to devote the rest of her life to the Lord. During her time in the monastery, she supported the election of Amalric as Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. She died some years later in Bethany. Thierry of Alsace died in 1168 and was buried in the abbey of Watten, near Saint-Omer.

When Thierry left for the Holy Land for the third time Sybilla came with him. On her arrival in Jerusalem, she separated from Thierry and joined the Convent of St. Lazarus in Bethany to devote the rest of her life to the Lord. During her time in the monastery, she supported the election of Amalric as Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. She died some years later in Bethany. Thierry of Alsace died in 1168 and was buried in the abbey of Watten, near Saint-Omer.

Thierry of Alsace and Sybilla of Anjou had a son named Philip who married to Elisabeth of Vermandois. It is this Philip who became the patron of Chrétien de Troyes. The marriage remained childless, and when Philip discovered Elisabeth had an affair, he had her lover beaten to death. In 1177, Philip joined the Second Crusade and ended up being offered the Kingdom of Jerusalem, because he was the closest male relative to King Baldwin IV the leper who was childless like himself. Philip refused claiming he was there only as a pilgrim. Philip of Alsace died in 1191 and was buried in the Abbey of Clairvaux.

Chrétien dedicated Perceval, the Story of the Grail to his patron, because he sowed the seed of the tale in such good soil that its greatness was ensured. There is something of a prediction in this claim, or better: the hint of a plan, a strategy. The poet states that his labours will not be in vain, he is merely fullfilling the count’s wishes. And so, from a book given to him by his patron, he will put into verse ‘the best story ever told in a Royal Court’. The only known story in Philip’s famliy that qualifies as such in is of course the Story of the Holy Blood brought to Bruges by Philip’s father Thierry. We could only have been sure if Chrétien hadn’t died before he could finish his poem.

The Glastonbury Connection

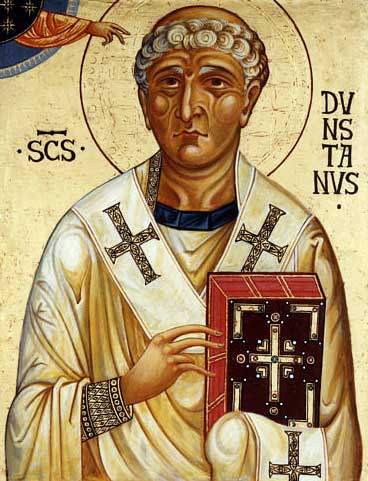

Saint Dunstan was once the Abbot of the famous Abbey of Glastonbury in England. As a young lad, while studying under Irish monks who lived in the ruins of the Abbey, Dunstan had had a vision of the Abbey being restored to its original splendour. In 943 he built a small cell adjacent to the old church of St. Mary. It was there that he went to study, do his handicrafts or play the harp. In the scriptorium he worked as a silversmith.

Saint Dunstan was once the Abbot of the famous Abbey of Glastonbury in England. As a young lad, while studying under Irish monks who lived in the ruins of the Abbey, Dunstan had had a vision of the Abbey being restored to its original splendour. In 943 he built a small cell adjacent to the old church of St. Mary. It was there that he went to study, do his handicrafts or play the harp. In the scriptorium he worked as a silversmith.

After he had become Abbot of Glastonbury, Dunstan started the reconstruction of the Abbey. He also established the Benedictine monasticism. Then in 995, when King Edwy had climbed the throne of England, he found the young monarch fornicating with a young girl and her mother. Dunstan forced the King to renounce the girl, and then realized he had provoked Edwy. With the King on his heels, he fled to his Abbey. Edwy looted the Abbey but Dunstan somehow managed to escape, fled England and crossed the channel to Flanders. There he was received by Count Arnulf and lodged in the Abbey of Mont Blandin near Ghent. The exile of Dunstan ended in 957, when Edwy himself had to flee for his brother.

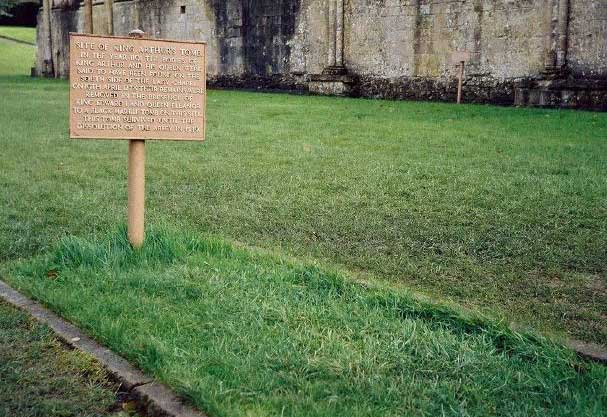

In his book In Search of England, the English writer Michael Wood suggests that the legends associated with Glastonbury like those of King Arthur and the Holy Grail had their origins with St. Dunstan. His leadership of the monastery, which eventually propelled Glastonbury into first rank among England’s great Abbeys, along with his Benedictine emphasis on learning, planted the seeds of belief in its unique importance as a spiritual centre of the nation. In the following centuries the Abbey got rich and powerful. At the time of Chrétien de Troyes’ death, Glastonbury monks discovered a hollowed-out log in the cemetery containing two skeletons. Behind the covering stone he found a leaden cross with an inscription reading: Here, on the Isle of Avalon, was interred King Arthur. The other skeleton had to be Guinevere, of course.

In his book In Search of England, the English writer Michael Wood suggests that the legends associated with Glastonbury like those of King Arthur and the Holy Grail had their origins with St. Dunstan. His leadership of the monastery, which eventually propelled Glastonbury into first rank among England’s great Abbeys, along with his Benedictine emphasis on learning, planted the seeds of belief in its unique importance as a spiritual centre of the nation. In the following centuries the Abbey got rich and powerful. At the time of Chrétien de Troyes’ death, Glastonbury monks discovered a hollowed-out log in the cemetery containing two skeletons. Behind the covering stone he found a leaden cross with an inscription reading: Here, on the Isle of Avalon, was interred King Arthur. The other skeleton had to be Guinevere, of course.

You could speculate that the book Philip had given to Chrétien to base his epic poem on, was brought to Ghent by St. Dunstan. Glastonbury was on the verge of becoming the center of Arthurian lore and Grail legend, while the one and only real Grail was held in Bruges. The Holy Blood of Christ, or maybe the “something” containing the secret of the bloodline, were brought there by the Templars, perhaps in two steps. The first in 1150 (perhaps as a document) and secondly, a century later, as the Relic holding the Holy Blood. The Grail castle was the ‘Burg’, (Dutch for ‘Castle’), the building that houses the Chapel of the Holy Blood.

In his article Bruges: the Grail City? Philip Coppens argues that Chrétien de Troyes wrote about a royal tradition concerning a precious Relic, carried in a procession, as has been done with the Holy Blood of Bruges for centuries. It is not unlikely that Chrétien’s patron asked the poet to write a romance to emphasize his personal relationship to the Holy Blood or the Holy Grail of Bruges.

Yearly Procession of the Holy Blood, Bruges

Bruges-la-Morte

In his poem Brugge (Bruges) the Flemish priest-poet Guido Gezelle (1830) described the city as a copy of the Holy Land, with its great Gothic churches called Jerusalem, Nazareth and Bethlehem. Being a citizen of Bruges himself, he didn’t forget to mention the Holy Blood that was brought there during the Crusades. The Jerusalem Church in the quiet St. Anna Quarter is arguably the most remarkable of the many churches dominating the Bruges skyline. It was built in the 15th century as a scale model of the Holy Sepulchre by Anselmus Adornes and his wife. It houses a rather morbid fake tomb of Christ. The Jerusalem Church is still there and is privately owned by the descendants of the Adorni family who were merchants from Genoa. In the 15th century, when the Jerusalem Church was built and Jan van Eyck painted his Mystic Lamb, the noble Brotherhood of the Holy Blood was founded. Is this only an alternative name for the famous Grail Brotherhood?

In his poem Brugge (Bruges) the Flemish priest-poet Guido Gezelle (1830) described the city as a copy of the Holy Land, with its great Gothic churches called Jerusalem, Nazareth and Bethlehem. Being a citizen of Bruges himself, he didn’t forget to mention the Holy Blood that was brought there during the Crusades. The Jerusalem Church in the quiet St. Anna Quarter is arguably the most remarkable of the many churches dominating the Bruges skyline. It was built in the 15th century as a scale model of the Holy Sepulchre by Anselmus Adornes and his wife. It houses a rather morbid fake tomb of Christ. The Jerusalem Church is still there and is privately owned by the descendants of the Adorni family who were merchants from Genoa. In the 15th century, when the Jerusalem Church was built and Jan van Eyck painted his Mystic Lamb, the noble Brotherhood of the Holy Blood was founded. Is this only an alternative name for the famous Grail Brotherhood?

The Holy Blood of Christ indeed seems to have turned medieval Bruges into a Holy City. It also kick started tourism to the city from the 19th century onwards. But maybe this Holy City is not as holy as it seems, just because of this Precious Holy Blood that… well, could be pretty unholy. As I described in my article Visiting Bruges-la-Morte, a medieval ghost city, the Holy Blood of Bruges was the reason why ‘the Powers of Good & Evil’ had to fight eachother more fiercely here than anywhere else in the world. If Bruges was chosen and designed to be a Holy City, then Satan perhaps had to unleash all his forces here to turn Bruges into a truly Unholy City.

The connection of Joseph of Arimathea with the Grail ‘“ being the cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper ‘“ dates from the late 12th century. Robert de Boron describes how Joseph receives the Grail from Jesus and brings it to Great Britain. Later writers recount how Joseph used the Grail to catch the Saviour’s blood.

The connection of Joseph of Arimathea with the Grail ‘“ being the cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper ‘“ dates from the late 12th century. Robert de Boron describes how Joseph receives the Grail from Jesus and brings it to Great Britain. Later writers recount how Joseph used the Grail to catch the Saviour’s blood.

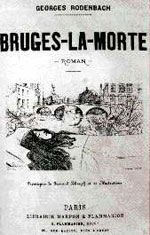

The Grail legends became a potent mix of Christian lore and Celtic mythology, some parts interwoven with the legends of the Holy Chalice. All these themes got even  further mixed up during the 19th century when ‘decadent’ writers like Georges Rodenbach and Joris-Karl Huysmans turned Bruges into ‘Bruges-la-Morte’, a Very Unholy City indeed.

further mixed up during the 19th century when ‘decadent’ writers like Georges Rodenbach and Joris-Karl Huysmans turned Bruges into ‘Bruges-la-Morte’, a Very Unholy City indeed.

In Bruges-la-Morte or The Dead City of Bruges, Georges Rodenbach tells the story of a widower who, overcome with grief, takes refuge in Bruges. There he becomes obsessed with a dancer in the opera by name of Robert le Diable who bears an exact resemblance to his dead wife. The novel was notable for its poetic evocation of the decaying city and raised some scandal because of the ‘decadent’ and ‘morbid’ atmosphere. The meeting (or mating) of Eros and Thanatos didn’t go down very well at the time either.

The Damned, Down There…

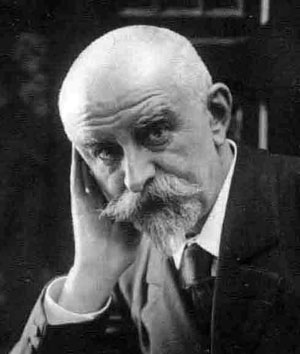

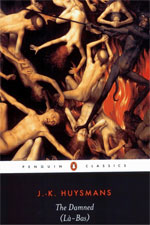

The decadents only caused a minor storm compared to the scandal raised by a certain Joris-Karl Huysmans. Born in Paris from a Dutch father, Huysmans published a novel LÃ -Bas (The Damned) in 1891, attracting considerable attention for his depiction of French Satanism. The novel introduced the character of Durtal, a thinly disguised alter ego of the writer, who would return in his later work to trace Huysmans’ conversion to Roman Catholicism. LÃ -Bas has a particularly vivid scene depicting a Black Mass:

The decadents only caused a minor storm compared to the scandal raised by a certain Joris-Karl Huysmans. Born in Paris from a Dutch father, Huysmans published a novel LÃ -Bas (The Damned) in 1891, attracting considerable attention for his depiction of French Satanism. The novel introduced the character of Durtal, a thinly disguised alter ego of the writer, who would return in his later work to trace Huysmans’ conversion to Roman Catholicism. LÃ -Bas has a particularly vivid scene depicting a Black Mass:

‘And thou, thou whom, in my quality of priest, I force, whether thou wilt or no, to descend into this host, to incarnate thyself in this bread, Jesus, Artisan of Hoaxes, Bandit of Homage, Robber of Affection, hear!… (…) Profaner of ample vices, Abstractor of stupid purities, cursed Nazarene, do-nothing King, coward God!’

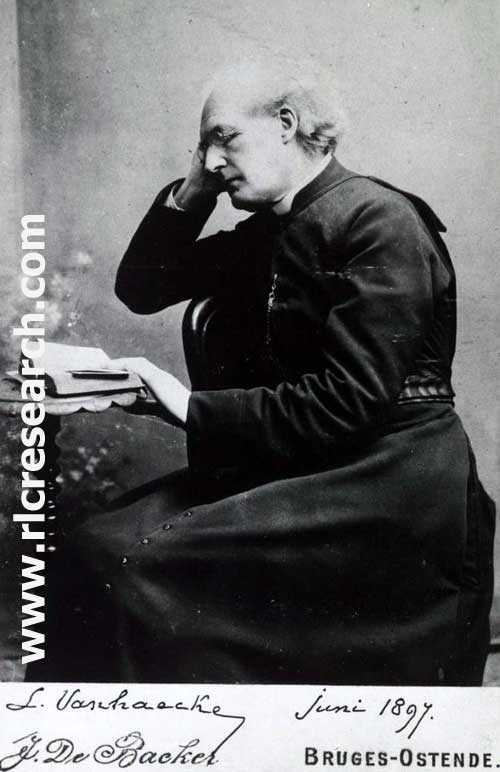

‘Yet the ultimate abomination of the nineteenth century must be that, disguised as fiction and yet widely recognized at the time as fact, reported by Joris-Karl Huysmans in his notorious novel LA-BAS,’ says Aubrey Melech in Missa Niger: La Messe Noire (Sint Anubis Books). ‘Indeed, so close to the abominable truth is this work that the Canon Docre, Huysmans’ Satanic celebrant, can be identified as the Belgian-born priest Louis Van Haecke, who died, if not in the odour of sanctity, at least at the advanced age of 84 in 1912.’ This Louis Van Haecke happened to be the Chaplain of the Holy Blood Chapel.

T.J. Hale, the translator of LÃ -Bas, states in his foreword that Huysmans was close friends with Berthe Courrière, an attractive woman who fed consecrated hosts to stray dogs and busied herself luring inexperienced confessors into sin by inventing all sort of erotic tales. She had a wide network of contacts in occultist and spiritualist circles. About a year after Huysmans first met her, Berthe got herself in serious trouble with the Belgian authorities. She had been found hiding in the bushes, clad only in her underwear. The police of Bruges was skeptical of the story she told them about a narrow escape from a satanic priest named Van Haecke and interned her in a mental asylum. It took the involvement of Remy de Gourmont, another friend of Berthe and Huysmans, to obtain her release.

‘The question of whether or not the author of The Damned ever attended a Black Mass is one which has been much debated by biographers and scholars. Hale says. ‘If he did, it was probably in the company of this same Abbé Louis Van Haecke, Chaplain of the Holy Blood at Bruges, who, like Canon Docre in the novel, was reputed to have a cross tattooed on the soles of his feet, so that he may have the pleasure of continually walking upon the symbol of the Saviour. Huysmans certainly cultivated the claim that he had attended such a ceremony (though he was also known to categorically deny it) and that it was there that he had first seen Van Haecke, who was not officiating but standing aside from the rest of the congregation. ‘I discovered many curious facts concerning this man,’ Huysmans declared. ‘He has paid three visits to Paris, where he moves in Satanist and occultist circles. On his second visit he stayed at the Hôtel Saint-Jean-de-Latran, in the rue des Saints-Pères, an establishment of doubtful repute which is known chiefly for its clientèle of renegade priests.’

‘The question of whether or not the author of The Damned ever attended a Black Mass is one which has been much debated by biographers and scholars. Hale says. ‘If he did, it was probably in the company of this same Abbé Louis Van Haecke, Chaplain of the Holy Blood at Bruges, who, like Canon Docre in the novel, was reputed to have a cross tattooed on the soles of his feet, so that he may have the pleasure of continually walking upon the symbol of the Saviour. Huysmans certainly cultivated the claim that he had attended such a ceremony (though he was also known to categorically deny it) and that it was there that he had first seen Van Haecke, who was not officiating but standing aside from the rest of the congregation. ‘I discovered many curious facts concerning this man,’ Huysmans declared. ‘He has paid three visits to Paris, where he moves in Satanist and occultist circles. On his second visit he stayed at the Hôtel Saint-Jean-de-Latran, in the rue des Saints-Pères, an establishment of doubtful repute which is known chiefly for its clientèle of renegade priests.’

Rennes-le-Château’¦ a Déjà Lu

Huysmans came to believe that the guardian of the Holy Blood of Bruges was the most evil man in Europe. Van Haecke surely displayed an appetite for ‘comparative religion’ but there exists no solid evidence that he indeed was the real demonic Canon Docre. Perhaps ironically, when LÃ -Bas was published and the story got around that Canon Docre was in reality the Chaplain of the Holy Blood, the Blood Chapel in Bruges attracted so many visitors that Van Haecke had to be replaced.

Huysmans came to believe that the guardian of the Holy Blood of Bruges was the most evil man in Europe. Van Haecke surely displayed an appetite for ‘comparative religion’ but there exists no solid evidence that he indeed was the real demonic Canon Docre. Perhaps ironically, when LÃ -Bas was published and the story got around that Canon Docre was in reality the Chaplain of the Holy Blood, the Blood Chapel in Bruges attracted so many visitors that Van Haecke had to be replaced.

The story of Louis Van Haecke reads like a déjà lu in comparison to the life and times of Bérenger Saunière, parish priest of Rennes-le-Château, who, in the same timeframe, allegedly got involved with the trendy occultist and maybe even satanist circles in Paris. The stories feature the same usual suspects like composer Claude Debussy and the Belgian symbolist playwright Maurice Maeterlinck, author of the ‘Merovingian Play’ Pelleas and Melisande.

One question remains in the dark shades of Bruges’ silhouet. How could the keeper of the Holy Blood of Bruges, perhaps even of the Holy Grail, lose faith to the extent that Louis Vanhaecke appears to have done, attending a gathering where the Man whose Blood he guarded was called “Jesus, Artisan of Hoaxes”.

Patrick Bernauw

edited by Corjan de Raaf

Patrick Bernauw is living in the Dutch speaking part of Brave Little Belgium. He is a full time writer of historical mysteries and faction thrillers, performer and mystery game producer.

Patrick Bernauw is living in the Dutch speaking part of Brave Little Belgium. He is a full time writer of historical mysteries and faction thrillers, performer and mystery game producer.

Some Bernauw links:

The Lost Dutchman’s Historical Mysteries

Patrick Bernauw’s Haunted World

©2007-2012 renneslechateau.nl, all rights reserved. Original photos and image Louis Vanhaecke copyright Corjan de Raaf. Bruges panorama by G. Batistini. Image of Bruges-La-Mort copyright Patrick Bernauw. All are reproduced here with kind permission

Fascinating article, with more substance than I usually read in stories about the Grail. Fascinating and informative.

this is the best grail article I have read in a very very long time.

This is the BEST english RLC-site in existence!

Chapeau!

Right on!

daag …

This line of reasoning makes a lot of sense. Intriguing food for thought. Raven (and Patrick of course), thanks for presenting yet another great article.

Thanks guys, really appreciate the support.

Take care | Raven

Raven,

One more point about who’s being vassal of whom:

I always thought that in the 12th century Flanders belonged to the Champagne. The article above states it’s vice versa. Do you know from when to when the Champagne belonged to Flanders?

Thank you in advance.

Thank you all for the great feedback!

Flanders: there were the first european Templar headquarters … and there’s also a connection to the holy grail.

In the last chapter of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Perceval poem figures the son of Perceval named Loherangrîn who left two childrent with his wife in Brabant before returning to the grail realms.

It seems that Wolfram knew something of certain flamish (primitive?) families. :)

Wolfram also called the Templars “Wächter des Grals”.

This is very true, Eginolf. I started with a more or less “close reading” of Chrétien’s Perceval in search of the “Flemish Connection”, but Wolfram’s Perceval also has some “disturbing” Flemish details: in those days Antwerp was a very small town – why Wolfram would mention it? Maybe his Grail wasn’t really a Pyrenean one?… But that’s something to write about in a new article, I guess!

Speaking of ‘Flemish families’, while reading up on the origins of the Lindsay clan and other prominent Scottish families associated with Freemasonry and the occult, I found that not everyone agrees on their alleged Norman origin. Apparently quite a few people believe these families to be Flemish in origin. A google search poduces quite interesting results on this topic.

Good job !

I shall be in Brugges in september.

Because of you, T.Y !

Philemon