A Man’s Best Friend

In the mystery of Rennes-le-Château, an enormous amount of attention is reserved for a very small group of people. At the top of the list of course is the man who embodies the mystery like no-one else: Bérenger Saunière. Where he found the money to build a veritable them park on the desolated hilltop of Rennes-le-Château in the south of France was and is still at the very heart of the enigma.

His fellow priests spent much time in the spotlight as well. Henri Boudet, the priest of Rennes-les-Bains is believed by some to have been Saunière’s puppet master and as such he and his book La Vraie Langue Celtique have been exhaustively researched. Antoine Gélis, priest of the neighboring village of Coustaussa was viciously murdered under suspect circumstances and also drew much attention. Similar attention was paid to Saunière’s maid Marie Dénarnaud, and to Monseigneur Billard, the Bishop that seemed to approve of his works, and finally Monseigneur de Beauséjour, his successor that brought him to trial in the eclestical courts of Carcassonne and Rome.

Only two of the above can be assumed with certainty to have known what and where the material treasure was, and if an immaterial treasure existed also. They are Bérenger Saunière and his life-long companion Marie Dénarnaud. Saunière confessed before he died but it is completely uncertain what he told his colleague Abbé Rivière of Espéraza. If he told anything, Rivière, who preformed Saunière’s last rites, appears to have kept his vow of secrecy for the confession. Marie Dénarnaud died more than 30 years later in January 1953. She appears to have spoken about Saunière’s secret in vague and broad terms, suggesting people were walking on gold without knowing and that Saunière could have fed the entire village for a very long time. In the end there really aren’t any open threads of investigation left that could draw on demonstrable first or even second hand information. Or is there?

Although Saunière created an impressive pile of letters and journals, he never once mentioned the source of his wealth. Sure, he made some petite and tantalizing references to it later in his life, but they might just as well be classified as statements of gentle irony; a trait he was well-known for throughout his life. One thing for sure, little appears to have been wrong or lacking with his sense of humor.

One such known occasion is when Antoine Beaux, Abbé of Campagne-sur-Aude was attending a dinner party at Saunière’s table. He remarked “My friend, to see you doing so well, one would think you found a treasure”. To this the host appears to have answered: “Me l’an donat, l’ai panat, l’ai parat é bé lo teni”. In French it means “Ils me l’ont donné, je l’ai pris, je l’ai apprêtré; eh bien, je le tiens bien.” An English translation would be: “They gave it to me, I took it, I made it work and I will hold onto it.”

Not withstanding these facts, I consider it likely that some people knew at least bits of Saunière’s secret, or perhaps secrets. The prime candidate is sometimes mentioned but no major investigations have been conducted into his life or legacy. Perhaps wrongly so. To whom would any man confide his secrets? To his best friend. Apart from his brother Alfred, Bérenger Saunière had but one true friend: Abbé Eugène Grassaud.

Grassaud advised Saunière on many occasions and in all sorts of matters. In fact their bond was so strong that he continued advising Marie Dénarnaud long after Bérenger had passed away. He wrote to her frequently, helping her with her finances and searching for a buyer for the estate in Rennes-le-Château. Is this ironic or what? The man’s best friend needed to give Marie financial advice because she refused or was unable to tap into the man’s resources, even though all of the Abbé’s possessions had been willed to her. All evidence suggests she knew very well what and where the treasure was but she destroyed all evidence and refused to discuss it.

Eugène Grassaud

Perhaps it is time we pay more attention to this well thought-of man and his many accomplishments. In doing so, perhaps we will uncover a trace of the secret he shared with his best friend. To kick off that journey I visited two important locations in his life; St-Just-et-le Bézu, where he was born, and St-Paul-de-Fenouillet, halfway between Rennes-le-Château and Perillos, for it is here that he left his most lasting impression.

St-Just-et-le-Bézu

St-Just-le-Bézu is a small village at the foot of the mountain and Templar ruins of Bézu. The few elderly people that remain in the village retain a vivid memory and oral tradition of events that occurred there over the last few hundred years. They speak about the turmoil caused by the French revolution and how the local priest purchased the properties of the fleeing nobles for blackmail prices, in order to become the richest man in the village, just prior to fleeing himself.

Guillaume Joseph Eugène Grassaud was born in St-Just-le-Bézu in 1859. His parents, Baptiste Grassaud and Marie-Louise Flamand were well respected members of the community. In the village, which houses only sixty souls today, there’s a tiny church that has a quiet down-to-earth nature to it and in which some Templar references can still be found, perhaps related to the proximity of the former Templar commanderie. Most remarkable are the two crosses on the altar that resemble Templar crosses but on closer examination appear to be made out of fishes or possibly pieces of rope.

Like most churches in the region, the church is adorned with the obligatory statues of St. Antoine the Padoue and St. Pierre, and of course St. Just, after whom the village was named, and of Ste Eugénie, after which Eugène Grassaud was named. Jeanne d’Arc is there too. The altar is one of the few original pieces in the church. All the rest had to be replaced after a priest destroyed the entire interior in a rage after the promulgation of the Separation of Church and State in 1905. Apparently he didn’t take that very well.

The altar in the small church of St-Just-et-le-Bézu

The Churches’ saints: St. Just, St. Antoine de Padoue, Jeanne d’Arc,

St. Pierre et Ste. Eugenie

The Church

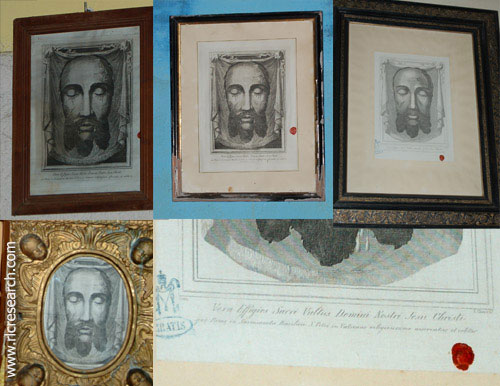

One last feature in the church is an engraving of the Sudarium from 1897, complete with the phrase:

VERA EFFIGIES SACRI VULTUS DOMINI NOSTRI JESU CHRISTI

QUAE ROMAE IN SACROSANCTA BASILICA S.PETRI IN VATICANO RELIGIOSISSIME ASSERVATUR ET COLITUR

The text translates as ‘Veronica’s print of the face of our Lord Jesus Christ, guarded in the Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican’. If you look hard enough, you can actually still buy a copy of this engraving in its original state on eBay. However the presence of the engraving is not remarkable as such, but it gains weight when you realize that many chapels in the region have this same print on the wall. I counted no less than four such examples in one day.

For instance in the village of Brenac, not far from Rennes-le-Château, the engraving has even been integrated into the altar of, the exquisite side chapel that was paid for by the Royal Notary Courtade, whose family left many marks in the town. It concerns the same Notary Courtade that in 1634 documented the location of the two famous tombs in Perillos that later featured on Saunière’s Model. It is well documented that Saunière visited Brenac and its church on many occasions.

The Sudarium engraving in St-Just-et-le-Bézu, Bugarach, St-Paul-de-Fenouillet and Brenac

St-Paul-de-Fenouillet

Young Eugène Grassaud was destined to go to Seminary school and was later admitted to Saint Sulpice in Paris, where he received a doctorate in theology. Shortly after, he returned to the south of France and began teaching in Perpignan. In 1900 he became the priest of Amélie-les-Bains, before finally settling in St-Paul-de-Fenouillet in 1908.

St-Paul-de-Fenouillet with its 14th century church

Grassaud was an erudite man. Saunière obviously held him in very high regard. In fact, he gave him one of the treasures of Rennes-le-Château’s church: a valuable gold Chalice, donated to the church by the Order of the Knights of Malta around 1750 (and stashed away in the church by his predecessor Antoine Bigou before he fled to Spain due to the Revolution, in 1792). It was Eugène Grassaud who advised Saunière to select Eugène Huguet as his support in church’s courts in Carcassonne and Rome.

There are many elders in St-Paul-de-Fenouillet who maintain vivid recollections of Abbé Grassaud. In fact, he made enough of an impression to have the square in front of the church named after him as late as 1972. His name also adorns the adjacent foyer, housing the small Sunday school. Grassaud was a learned man by any standard. He was a fanatical librarian and historian, who did considerable research into the history of the village and its surroundings. His personal library contained many rare medieval documents that he would study for long periods of time. He wrote in an archaic Latin. The 14th century church of St-Paul was very important to him. He went as far as to buy the adjacent houses, demolishing some of the slums immediately around the building. He laid down his duties in 1945 when he felt his end was near. He died one year later in the village of Caudiès-de-Fenouillèdes, where his brother maintained a doctor’s practice in the family home.

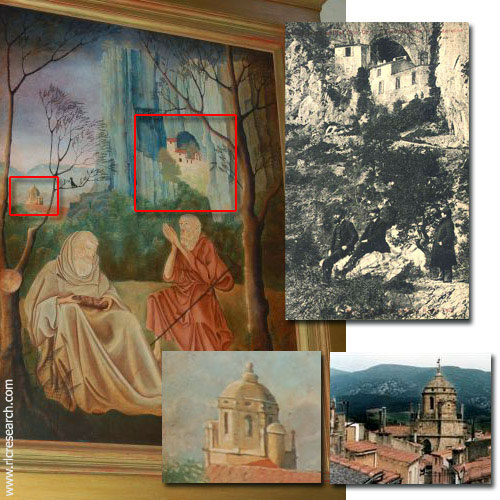

The rich history of the area includes the Gorges du Galamus, the long ravine stretching all the way from Bugarach to St-Paul. In 1782, during a gangrene epidemic, the young men of the village went to what was called the Cave of the Magdalene with a relic of St. Antoine to ask the saints to rid them from the disease. Soon after the disease disappear from the village. They built a hermitage and a small chapel on the site. The event is remembered by a painting in the church.

Temptations of St. Anthony with clear references to the Hermit’s retreat in the Gorges du Galamusand the village of St-Paul-de-Fenouillet

During his life Grassaud had numerous works carried out on his church. In addition to restoring new statues and a new confessional, he had a number of enormous frescos painted on the walls. Unfortunately, they have been covered up after his death because the villagers didn’t like them very much. What remains is still an extraordinary church with some beautiful furnishings and tableaux. We have only started the surface of the life and works of this extraordinary man. Next step will be to go into his library and archives.

The Altar

Pieta

Mary of Seven Sorrows

This article was published on Andrew Gough’s Arcadia.