Guillem de Gellone (755 – 814) in French, also known as William of Orange or William with the Short Nose, after a legend in which a Saracen cut off part of William’s nose in battle.

Guillem de Gellone (755 – 814) in French, also known as William of Orange or William with the Short Nose, after a legend in which a Saracen cut off part of William’s nose in battle.

William’s mother was a daughter of Charles Martel, making William a cousin of Charlemagne, at whose court he spent his youth. His father Theodoric (Thierry IV) was the Count of Autun and Toulouse and is said to have been of Merovingian descent.

Being King of Septimania. William of Gellone is one of the pivotal characters in the controversial book Holy Blood, Holy Grail by Henry Lincoln, Michael Baigent and the late Richard Leigh. In the book it is claimed that the Merovingian bloodline descended from Jesus and Mary Magdalene, making William a Jew of Royal Blood. Their main source of information was the book A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France (1972) by the American historian Arthur Zuckermann. Zuckermann claims that William was indeed of Jewish descent. Local folklore would indicate that he was of the House of David. William was said to have respected Sabbath even during battles, had the Lion of Judea in his Coat of Arms and spoke Arab and Hebrew fluently. This carries extreme relevance in relation to Lincoln, Baigent & Leigh’s theory that the Holy Grail represents the Holy Bloodline of family descendance from the biblical King David through Jesus and Mary Magdalene into the Royal French Merovingian Dynasty.

William of Gellone, donating Charlemagne's relic of the True Cross to the Abbey of Gellone. Painted by Étienne Loys, 18th century, currently in the church of Vendémian.

In 790, after his father had died, Charlemage confirmed William in descending his father as the second Count of Toulouse. He took up arms against the army of the Moor King Hisham I who had proclaimed Holy War against the Christians and penetrated the Languedoc as far as Narbonne. He is most famous for defeating the Arab forces in the area around Orange on 30th April 800. After many years of fighting, the Muslims retreated back into Spain, discouraged by Willliam’s attitude of never giving up. William ended his military career reconquering the territories around Barcelona in 803. Among the many titles he gathered was ‘Count of Orange’ (the first one) and ‘Count of Razès’. The Razès, the county of which the later Rennes-le-Château (then named Rhedae) was part was founded in 785 by Charlemagne. He made William the first titular Count. It was probably William and his sons who fortified Rhedae in the eary 800s.

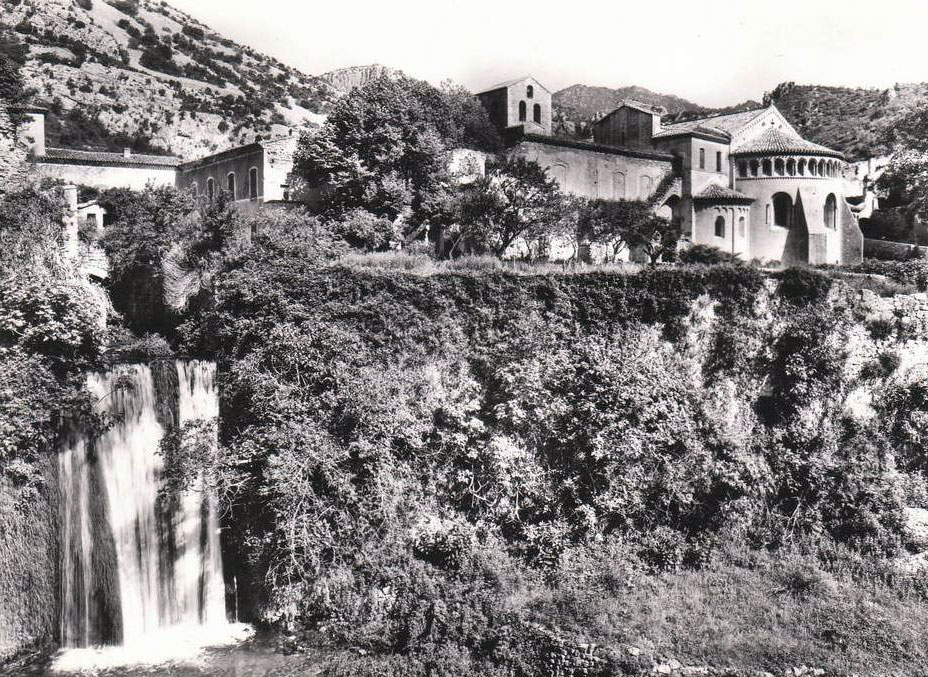

In 804 William founded what is now known as the Benedictine Abbey of Gellone in the French town of St. Guillem-le-Désert. He had been inspired to do so after he had found back his childhood friend, St. Benoît of Aniane, himself a vassal of Charlemagne. Initially, the Monastery was called Monastery of St. Crucis in Gellone, after a relic donated by Charlemagne containing a piece of the true cross which is still there today. In 806 William withdrew from civil and public life and entered the Monastery he had founded himself. According to Zuckermann, during this period of his life William was initiated in the ancient Jewish Kaballah and the rites of personal transmutation. He is said to have died in the Monastery on 28th May 814, before Charlemagne. That date is disputed by some scholars based on a document by Dhuoda, wife of Willam’s brother-in-law Bernhard of Barcelona. In her ‘Liber Manualis’ that she kept until 843 for the benefit of her son, she mentions all her deceased relatives. The most famous of all, William, isn’t mentioned, implying that he was alive at least until 843.

In 804 William founded what is now known as the Benedictine Abbey of Gellone in the French town of St. Guillem-le-Désert. He had been inspired to do so after he had found back his childhood friend, St. Benoît of Aniane, himself a vassal of Charlemagne. Initially, the Monastery was called Monastery of St. Crucis in Gellone, after a relic donated by Charlemagne containing a piece of the true cross which is still there today. In 806 William withdrew from civil and public life and entered the Monastery he had founded himself. According to Zuckermann, during this period of his life William was initiated in the ancient Jewish Kaballah and the rites of personal transmutation. He is said to have died in the Monastery on 28th May 814, before Charlemagne. That date is disputed by some scholars based on a document by Dhuoda, wife of Willam’s brother-in-law Bernhard of Barcelona. In her ‘Liber Manualis’ that she kept until 843 for the benefit of her son, she mentions all her deceased relatives. The most famous of all, William, isn’t mentioned, implying that he was alive at least until 843.

William was twice declared a saint, the last time by Pope Alexander II in 1066.

Death of William of Gellone by Étienne Loys 18th Century, currently in the church of Vendémian

St. Guillem-le-Désert soon became an important place of pilgrimage. How important St. William became can be deducted from the fact that Count Raimbaut II visited St. William’s tomb before he left for the Holy Land as one of the leaders of the First Crusade in 1096.

Especially his victory in Orange made William subject of and in epic works like La Geste de Garin de Monglane, Dante’s Divina Commedia, Speculum Historiale by Vincent of Beauvais, and Willehalm, an unfinished epic romance by Wolfram von Eschenbach, better known for his most famous work Parzeval. Wolfram notably writes that the Grail castle was to be found in the Pyrenees, in the area that was owned by William of Gellone in the 9th century.

Especially his victory in Orange made William subject of and in epic works like La Geste de Garin de Monglane, Dante’s Divina Commedia, Speculum Historiale by Vincent of Beauvais, and Willehalm, an unfinished epic romance by Wolfram von Eschenbach, better known for his most famous work Parzeval. Wolfram notably writes that the Grail castle was to be found in the Pyrenees, in the area that was owned by William of Gellone in the 9th century.

In his book Wolfram von Eschenbach und die Wirklichkeit des Grals, the Swiss scholar Werner Greub published the results of a life-long study into the works of his teacher Rudolf Steiner. Greub considered Von Eschenbach’s Parzifal as the only veritable Grail account. After long and meticulous research, Greub concluded that William of Gellone had been Von Eschenbach’s primary source of information. William was the character Wolfram had named Kyot de Provence. Von Eschenbach later dedicated his monumental work Willehalm to William of Gellone.

Some of Werner Greub’s research into the real life sites of the Grail as described by Wolfram von Eschenbach is available online in English on the Willehalm website.

Archaeologist Brigitte Gibrac-Lescure suggests that the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Rennes-le-Château might have been founded by Guilemme de Gelone in the IXth century judging from the similarities between the design of the Knight’s Stone, the Visigothic altar pillar and similar features in the Abbey of St. Guilhem-le-Désert.

The descendants of William of Gellone lost the Razès in 844 when the county was transferred to the Counts of Carcassonne.

Images of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert

There are a couple of comments about William of Gellone already posted on the page containing the article, Was the body of Christ laid to rest in southern France? in case anyone is interested…

New thoughts by Gibrac-Lescure – new food. Just great!

You write:

“William of Gellone had been Von Eschenbach’s primary source of information. William was the character Wolfram had named Kyot de Provence.”

But:

Other writers of the same theosophic Steiner group that Greub comes from, wrote (i.e. von Stein in 1929, Meyer in 1956) that the character Kyot de Provence has been actually the troubadour Guillot de Provins.

BTW.

This same von Stein has been the source for the notorious Ravenscroft’s book “Spear of Destiny” (1972). Von Stein said that he talked to Hitler in 1911 about his visions Hitler supposedly had infront of that holy lance in Vienna.

… what goes around, comes around … (Doctor John Mac Rebenack) :))

To draw a line from Wlliam to Berenger:

There have also been the Penitents Blancs in the town of St. Guillem-le-Désert, they might be still there after all! They held (hold?) a branch in Limoux too and Sauniere might have been there, who knows.

;) :)

The writers mentioned who identify Kyot as Guillot de Provins are not from a theosophic, but an anthroposophic group around Rudolf Steiner. One of these writers is not Von Stein, but Walter Johannes Stein, writer of the book “The Ninth Century – History in the Light of the Holy Grail”. None of them have done any orginal research into this specific Kyot question, in contrast to the anthroposophist Werner Greub, whose book on Wolfram von Eschenbach I have translated into English (“How The Grail Sites Were Found”, new book version is in preparation) and also into Dutch (“Willem van Oranje, Parzival and the Grail”). None of them can bank (directly) on Rudolf Steiner’s work in this case, because he only affirmed that this Kyot was a historical personnage and not a figment of Wolfram’s teeming imagination as most scholars still tend to believe. But because Rudolf Steiner also stated that the Parzival story took place, not in the 12th but in the 9th century, Wolfram’s source Master Kyot could not, in his eyes, haven been this Guillot, as he is a figure from the 12th century.

The “notorious” book mentioned by Ravenscroft is not all a pack of lies, as some e.g. Christoph Lindenberg have maintained. Problem was that Ravenscroft originally wanted his book to be published as a dramatized version of the events described in it and not as a genuine historical work. The publishers however promoted it as such out of commercial grounds, which was apparently never the intention of the author. So e.g. Ravenscroft’s claim that Rudolf Steiner acted as a medium between the deceased General von Moltke and his wife on earth, is vehemently denied by Lindenberg, actually a true statement in the ligh of documents that later appeared. In the appendix to my English translation of Greub’s book on Wolfram, available on my webiste under Grail Sites, I have rebutted point for point the scathing critism that this Lindenberg in the same review leveled against Greub.

Greub’s book was actually meant as the first volume of a Grail trilogy from the age of Zarathustra to Rudolf Steiner, but the 2nd and 3rd volumes were never published by the Goetheanum in Dornach, the Free School for Spiritual Science, but many years later by Greub’s son Dr. Marcus Greub. (Why this is, or may be, I have related in my introductions to the various editions to the Grail Sites book as can also be read on my website.) These two volumes contain many interesting albeit controversial items of original Grail research, including an alternative version to the mistaken theory that Jesus Christ and Mary Magdelene had children, and also an exact dating of the nativities of two so-called Jesus children, who are mentioned in Lucas and Matthew with different geneaologies (the Lucas child stemming from God, Adam and then later Nathan – the priestly line from David, and on the other hand the Matthew child stemming from Abraham and from Salomon – the royal or kingly line from David).

P.S. The unsubstantiated claim, first made by the writers of “Holy Blood, Holy Grail”, that Wolfram wrote that the Grail castle from his “Parzival” is to be found in the Pyrenees is nowhere to be found in Wolfram’s work itself. Montségur was most probably in the 12th and 13th century a Grail castle, of which there were many, but not Wolfram’s Grail Castle Munsalvaesche, which according to Greub’s research was located in the Arlesheim Hermitage, an ancient Celtic holy place, near the Swiss town of Basle. Last point: the claim based on Dhuoda’s Carolingian education manual for the upbringing of her son, that William of Gellone was still alive in 843, because of the “fact” that she does not mention him as one of the deceased family members, does not hold, because as I once mentioned to Greub, Dhuoda’s manual does mention William as deceased. His laconic response was that then also this document must be a forgery…