Uomo Universalis

France mourned when Jean Cocteau died on 11 October 1963. In one blow, the country lost a great and internationally acclaimed poet, novelist, dramatist, designer and film maker. His fame began in his twenties and lasted until today.

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963)

Cocteau was a truely universal artist, who seemlessly combined forms of art during an enormously productive life. The great volume of works we can see today are of a consistent quality and coherence. It is no secret that Cocteau was more than moderately interested in things of an esoteric nature. It has often been suggested that there is more to see than you can see in some of his work. Others have gone even further. Pierre Plantard, in his ‘Dossiers Secrets‘ claimed Cocteau was a Grandmaster of the Priory of Sion, and thus protector of the ancient Merovingian Bloodline. The bubble of the ‘Dossiers Secrets‘ was burst in recent years but not the attention for the more enigmatice angle of Jean Cocteau’s work.

Fingers Crossed

There was a bizar incident surrounding his death that linked the master straight to the mystery of Rennes-le-Château. It was described in ‘Les Carnets Secrets’ in April 2006 by French researcher Jean-Luc Pergault. It involved Rennes-le-Château researcher Jean Brunelin. Brunelin, who was a photo journalist at the time. Soon after the artist’s death a long line of friends, celebrities and reporters came to his house in Milly-la-Fôret, where they were allowed in the room where Cocteau was laid in state. Brunelin made his photos and left. Several years later, when he had become interested in the mystery of Rennes-le-Château, he noticed the similarity between the strangely crossed hands of Cocteau lying in his coffin and the similarly crossed hands of Mary Magdalene on the bas relief of Saunière’s altar. He was then stupified to find out that on earlier photos of the deceased, made by his colleague photographers, Cocteau’s hands had been folded in the normal usual fashion. It meant that some time after his death, someone had re-arranged the hands on the dead body into this position. This cannot have been achieved without substantial force or even dislodging or breaking the fingers. Why did someone go through the pain of violating a dead man’s body. It was obviously of great importance for someone to make sure Jean Cocteau would enter his grave with his hands in this position: the crossed hands of an initiate.

At the top: Mary Magdalene with the fingers of her folded hands crossed 90 degrees on the bas relief of Saunière’s altar in Rennes-le-Château – At the bottom: Jean Cocteau lying in state as photographed by Jean Brunelin, with his hands forced into a very similar position (copyright Jean Brunelin)

The Master Phoenix

Like many artists, Cocteau struggled with conflicting desires and duties during his life. He combined a fight against a severe opium addiction with his homosexuality and strongly catholic belief. All these themes found their way back into his work. Cocteau decorated several churches and chapels during his life, the best known probably being the chapel of Saint-Blaise des Simples near his home in Milly-la-Fôret. He was buried in it amidst the murals he had prepared for this purpose himself. His self chosen epitaph was ‘Je reste avec vous‘ or ‘I remain with you‘. The master appears to have been looking forward to life after death and wasn’t afraid he would entirely disappear. He longed to be free in time and space. On multiple ocassions he stated he had been alive before and would be again. He believed in portals like mirrors through which humans could transcend time and space. He used that theme in several works, the most prominently in the ‘Testament of Orpheus’, an early version of ‘Back to the Future’. Several séances have been documented in which he talked to the dead. He often used a term he borrowed from his friend Salvador Dali: Phoenixology; to die and rise in a perpetual motion. Inversions where another thing frequently used in his work. By using the already mentioned mirrors, mirror images but also by sometimes talking and writing backwards in his plays films. Here too lies a parallel with the works of Abbé Saunière how masterfully worked a number of inversions in his church, garden and allegedly the inverse model of the Sacred Landscape of Perillos. If there’s any kind of proof that Jean Cocteau played a role of distinction in esoteric or even masonic circles, it is perhaps that he portraid himself as such frequently at all ages.

Left: Jean Cocteau in his twenties in a Masonic pose – Right: bust of Cocteau in his birth place Villefranche-sur-Mer in the same pose, signed by himself with his name and a pentagram

The Chapel of St. Peter

As said earlier, the first Chapel Cocteau decorated in full both inside and out, was the Chapelle St. Pierre in Villefranche-sur-mer. This chapel dating from the mid 16th century was used as a storage space for fish fillets when Cocteau started to transform it back into a place of worship. The artist was very active in this area. He had fallen in love with the idyllic bay when he arrived there in 1925 to stay in the ‘Welcome Hotel‘ for his first attempt at opium detoxification. The lighthouse of Cap Ferrat on the other side of the bay figured in his film ‘the Testament of Orpheus’ . It was on this cape that his patrones Francine Weisweiller, whom he met in 1950, had her estate which he also partially decorated. It was also here that he got in touch with the Rothschildts, whose ancestral estate lay a stone’s throw down the road.

The Village of Villefranch-sur-Mer at the French Côte d’Azur, with the Chapelle St. Pierre

Left: Cocteau poster from 1957 and admission ticket Right: dedication on the front wall from 1964

The Inversed Pentagram

Cocteau worked on the chapel for two years from 1956 to 1957. He dedicated the chapel to St. Peter (Pierre), the fishermen and life at the Mediterrenean. In total he painted 5 scenes in chalk, later sealed with paraffin wax. He was helped by an army of local artisans. A lot has already been said and written about the Chapel of St. Pierre. I will therefore restrict myself to some pictures and corresponding observations.

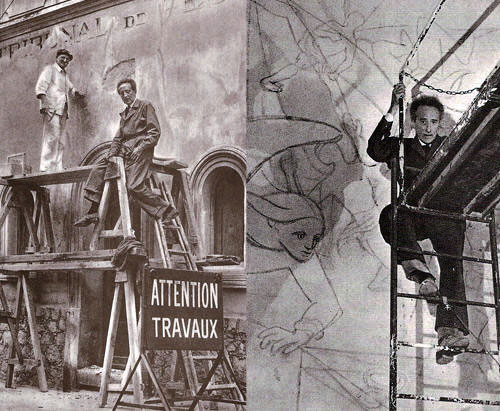

Left: Cocteau posing with a local builder who is working on the entrance of the Chapel Right: the artist at work on a mural on the inside

In the Chapel, there are five tableaus. Two of them depict life in the Mediterranean, three show scenes from the life of St. Peter, patron of fishermen.

Interior of the Chapel facing from the back to the entrance

One of the scenes depicts how Peter is taken captive after he has denied Christ for the third time. The cock who has crowed to indicate that block the ladder to heaven. In the bottom right corner, a woman, perhaps the wife of Pilate or someone close to Christ and his disciples is secretly watching through her fingers, or are we looking at an inversed ‘M’ here. With a bit of fantasy references could be made to the Perpignan and Gerona-based religious sect of La Sanch or La Sang, since a number of their symbols are on display here. The ladder, the cock and the roman legionairs.

Detail of the left side panel depicting Peter being taken captive after denying Christ three times

The most prominent mural is spread out over the back of the Chapel and depicts St. Peter walking on water. With Villefranche-sur-Mer in the background, he is unaware of the angel who is actually carrying him. Christ smiles at him benevolently. The trapezoid shaped altar was crafted by M. Giovanetti out of one block of stone. The candle holders and cross where made by Cocteau himself. He called the candle holders ‘the candlesticks of the Apocalypse’, a design which comes back several times in the Chapel. In the middle of the iron cross is the masonic triangle in a direct line with Peter’s mouth when he is still lying in the water.

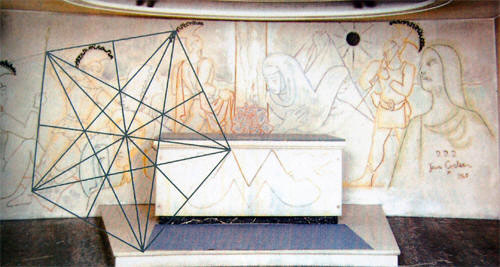

Saint Peter walking on water behind the trapezoid altar

It is whispered Cocteau had a meaning when he chose to paint five tableaus. Five as in the five points of a pentagram. Looking at the trapezoid altar and the way the woman on the left is looking diagonally up at Christ, it is not so hard to distinguish the lines of indeed a pentagram in the back of the church. The iron altar cross that Cocteau crafted himself is right in the middle. Looking at the trapezoid altar and the way the woman on the left is looking diagonally up at Christ, it is not so hard to distinguish the lines of a pentagram in the back of the church for the habitual Rennes-le-Château researcher. The iron altar cross that Cocteau crafted himself is right in the middle. The fact that the Master signed his name on the bust, only a couple of metres from the Chapel with an identical pentagram appears to indicate that it is there deliberately and on purpose.

The inversed Pentagram hidden in the back of the church by Jean Cocteau

Henry Lincoln, in his book The Holy Place claims Cocteau hid a pentagram in his mural in the church of Notre Dame de France (London, UK). He put his own head in the middle of it.

The pentagram hidden in the mural of Notre Dame de France with Cocteau’s self-portrait in the middle (picture copyright Henry Lincoln)

Cocteau was perhaps trying to tell us something from the initiate to the layman. His last big work might well hold the clue to the great knowledge Cocteau took to his grave with him. However, not before sharing it with a group of people who, hours after his death, made sure his hands were fixed in secrecy for eternity.

Sources: Mairie de Villefranche-sur-Mer

‘Guide sentimental et Technique à l’usage des visiteurs de la Chapelle Saint-Pierre’, Jean Cocteau 1957

‘Jean Cocteau: Man of the 20th Century‘, Tracy Twyman

‘Les Carnets Secrets‘, No 5, Avril-Juin 2006

Original photos copyright J. Gasiglia à Villefranche-sur-Mer et Paris-Match

Could Salvador Dali have been involved in Tartan Rennes -le – Chateau’s http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDS5kDHEudw