The Chapelle St. Pierre in Villefranche-sur-Mer was the first in a row of Chapels and Churches Jean Cocteau adorned with his characteristical man size murals. He created stained glas windows for the Church of St. Maximin in Metz, murals for the church of Notre Dame de France in London and the Chapelle Saint-Blaise in Milly-la-Forêt, his last resting place.

Left: the Chapel at Milly-la-Fôret that Cocteau decorated and in which he is buried, Right: the stained glass window he made for the church in Metz

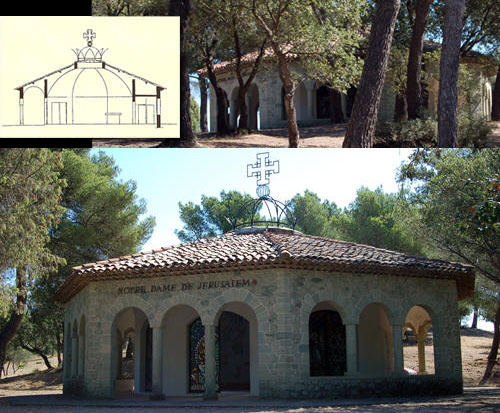

Little is it known, that when Cocteau died he was working on a final Chapel project. It concerns a chapel he designed from scratch including the remarkable octagonal floorplan: the Chapel of Notre Dame de Jérusalem in La Tour de Mare.

Forming an Eight

La Tour de Mare (the tower at the sea) is a tiny village near Fréjus at the French Côte d’Azur. It is some 60 km’s from Villefranche-sur-Mer, where Cocteau painted his first Chapel as described in an earlier post. The area in which it was built was bought in the early sixties by a very rich and influential banker and freemason from Nice called Jean Martinon. He intended the grounds as an artists colony, an ideal city. He called Jean Cocteau for help who set out to draw up the plans and designs for a Chapel, assisted by architect Jean Triquenot. Cocteau died in 1963, leaving the project unfinished but with all sketches and plans ready. The project was finished by his close friend and artistic heir Edouard Dermit who finished the last parts of the murals and Roger Pelissier who did the ceramics for the floor mosaic. The difference in style between Cocteau and Dermit is quite apparent in the various tableaus inside.

Notre Dame de Jérusalem, La Tour de Mare

In religious symbolism, the octagon or the figure 8 represent resurrection, rebirth and eternal life. Jesus’ resurrection took place eight days after his arrival in Jerusalem. Today this symbolism can still be seen in many baptismal fonts in churches all over the world. It is also the shape of the Dome of the Rock, housing the sacred stone that allegedly once supported the Ark of the Covenant.

The building is literally crowned with an iron construction in the shape of a crown. The Chapel is a veritable treasure trove of religious and esoteric imagery. Outside there are magnificently bright and colorful mosaics. Pièce de resistance however, without any doubt is the 360 degree panoramic mural on the eight walls and ceiling of the Chapel’s inside. It’s literally all around you and quite overwhelming when you first see it. It’s adorned by a beautiful floor mosaic. You can get a perfect impression of the Chapel by using the panorama viewer below. It requires the free Quicktime application to be installed on your computer.

[qt:http://crip.myahk.nl/DeRaaf/chapcocto.mov 600 300]

The Order of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre

The four smaller crosses are said to symbolize either the four books of the Gospel or the four directions in which the Word of Christ spread from Jerusalem. Most frequently however the five crosses symbolize the five wounds of Christ during the Passion. It is here that the Arma Christi come to mind again. The association with Christ’s wounds seems very relevant here given the content of the murals that mostly depict scenes from the Passion of Christ.

From left to right: Crusaders

Some of the appearances of the Jerusalem Cross in Cocteau's chapel

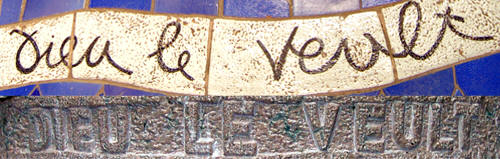

God Wills It

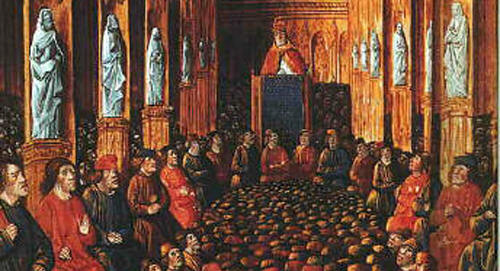

The Jerusalem Cross is not the only thing that refers to the Crusades and the Crusader Kingdom. Cocteau appears to have adopted the motto of the First Crusade for his Chapel. At the Council of Clermont in November 1095, pope Urban II held what must have been one of the most powerful speeches in history. A French Nobleman himself, he summoned the French nobility to free the Holy Land and the Holy city from the hands of the Persians. His words that survive today leave little to the imagination:

“You, who sell for vile pay the strenght of your arms to the fury of others, armed with the sword of the Machabees, go and merit an eternal award. If you triumph over your enemies, the kingdons of the East will be your reward. If you are conquered, you will have the glory of dying in the very same place as Jesus Christ, and God will never forget what he found you in the Holy Batallions.

This is now the time to prove that you are animated by true courage, the time to expiate violence committed in the bosom of peace, the many victories purchased at the expense of justice and humanity. If you must have blood, bathe in the blood of the infidels. I speak to you with harshness because my ministry obliges me to do so. Soldiers of Hell, become soldiers of the living God!

His speech was answered by a loud roar from the crowds. The northerns shouted ‘Dieu li volt!’; the southerns in their own tongue: ‘Dieu le veult!’.

Pope Urban II adressing the masses at the Council of Clermont (November 1095)

It is this last motto that is embedded in the floor and the altar of the Chapel, the most holy spot. It is so prominent you can hardly escape from the feeling that the artist must have had a very specific meaning here.

The Murals

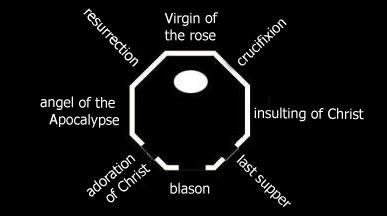

The eight walls of the octagon are decorated with as many tableaus:

1. The Last Supper

In the last supper we see Jesus, surrounded by his twelve disciples. It’s hard to tell who is who. The grouping doesn’t match Da Vinci’s last supper in Milan so we can’t identify the apostle from there. Christ is in the middle. A female figure is leaning against his shoulder on the right, probably John or perhaps Mary Magdalene. Judging by the face, the size and the dress, the figure is androgynous to say the least. We know John has been depicted with some femininity through the ages. On the other hand, the gospels state clearly that Mary Magdalene was present at the Last Supper, so why couldn’t she have been at the table? Remember that in the early 60’s it wasn’t fashionable yet to stage Mary Magdalene besides Jesus as his wife or mother of his children; Jean Cocteau couldn’t have been influenced by Holy Blood, Holy Grail or The Da Vinci Code. If the figure is indeed John or Mary Magdalene, there is an inversion going on, since he (or she) is usually depicted on Christ’s left. For the remainder of the article I will call this figure Mary Magdalene. Although I can’t be 100% sure I think the figure is more feminin than masculin.

In front of Christ there’s a glass of what appears to be red wine often symbolising blood. Perhaps Cocteau is confirming the fact that the Grail and the Holy Blood are in fact one. This too in an age where the translation of San Graal into Sang Real hadn’t been invented yet.

The last supper

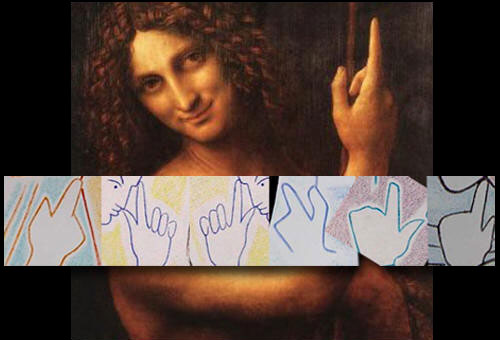

The apostle on the far left makes an inversed ‘J’ symbol. In fact the ‘J’ symbol is everywhere in the murals. It is also in the large mural of St. Peter walking on the water in the Chapel of St. Peter in Villefrance-sur-Mer (see earlier post). The gesture is often called ‘the gesture of John’, after Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous painting of John the Baptist (not to be confused with John the Apostle), noticeably it was also Da Vinci’s last painting.

Hands displaying the John sign

Cocteau shamelessly inserted himself into the scene of the Last Supper. It was not the first time he put a self portrait in a religious mural (Notre Dame de France, London), but this time he painted not only himself but also his muse: the French actor Jean Marais. It was whispered that the homosexual Cocteau and Marais shared more than the films they made together. Certainly Cocteau became a father figure for Marais. After Cocteau’s death, Marais would describe his first meeting with Cocteau as his ‘rebirth’. In that sense it’s very appropriate to find him in the Octagon, which represenst that very theme.

What is remarkable is that both in Notre Dame de France and Notre Dame de Jérusalem, Cocteau is looking away from Christ. From the dead as well as the living. Why would Cocteau, who was known as a religious man, do such a thing? Moreover, his friend Jean Marais appears to be mocking Christ with his gesture.

From left to right: Cocteau self portrait ND de France (London, UK), Coctau sel-portrait as part of the last supper (ND de Jérusalem), portrait of Jean Marais as part of the same last supper, Jean Marais as part of the same last supper, Jean Marais

The last supper with the

When you look at the scene for a while, you notice something weird. Apart from young Cocteau, nobody actually looks at Christ. Christ’s right eye is a little lower than his left, implying that he is looking at the figure leaning against his shoulder: Mary Magdalene. Closer inspection of the angles of the other figures’ eyes reveal that not only the older Cocteau, but also some of the other apostles are not looking at their Lord Jesus but at Mary Magdalene. When you count them, there appear to be five apostles looking at Mary Magdalene. Jesus is showing us his full hand as if he want to say: ‘Five’. From the previous article we know that Five was an important number for Jean Cocteau.

The fact that five apostles are not looking at Christ but at Mary Magdalene is an intriguing bit of information. The plot thickens when you combine it with the ‘J’ and inverted ‘J’ hand gestures that some of the disciples are making here, including Mary Magdalene himself.

Five apostles looking at Mary-Magdalene

2. Insulting of Christ

This is the scene from the Passion, where Jesus is mocked by and given the Crown of Thorns. This part of the mural doesn’t have the specific distinguished style of painting of Jean Cocteau. It’s likely it was done by Edouard Dermit. Cocteau was very specific in his sketches so the scene should be displayed as he intended.

We see two figures mocking Jesus. One is clearly a Roman soldier, the other one probably a jew, judging by his dress. Christ’s hands are tied and his left hand makes a peculiar gesture, as if imitating a walking mouse. On the right we see a woman praying with her eyes closed and face turned away from Christ, perhaps Mary.

Insulting of Christ

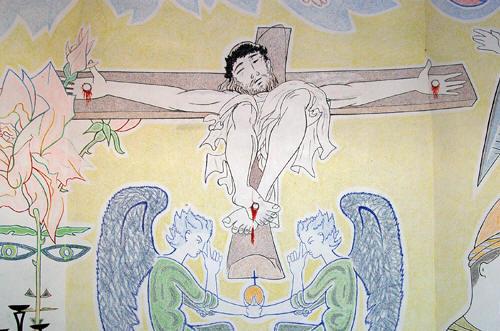

3. The Crucifixion

This too appears to be the work of Dermit. The crucifixion is depicted from an unfamiliar angle, looking up from the bottom of the cross. Two mirrored angels make the ‘J’ and inversed ‘J’ gesture, while holding the cross bearing Orb or Globus Cruciger. It normally symbolises Christ’s dominion over the world. In this context, with the angels holding it, making the gesture at the feet of the dead Christ it could have a different meaning alltogether.

Crucifixion

4. The Virgin of the Rose

Over the door leading to the small Sacristie, a mural is painted of a crowned woman, whose crown is overgrown with rose stalks. She is looking sadly into the direction of the Blason over the front entrance. Two giant roses adorn her on both sides. From the Middle Ages, the rose was seen as the queen of flowers, symbolysing the Virgin Mary. What is odd here is that normally she is represented by a thornless rose to indicate she is without sin. Not so here, her crown is oovergrown with thorny stems. What was her sin?

Virgin of the Rose

Perhaps her sins had to do with what’s depicted below her on the door leading to the Sacristie. A very vague sketch appears to display an image of the infant Jesus. Combined the pictures suggest Mary in relation to perhaps a sinful (natural?) conception of baby Jesus.

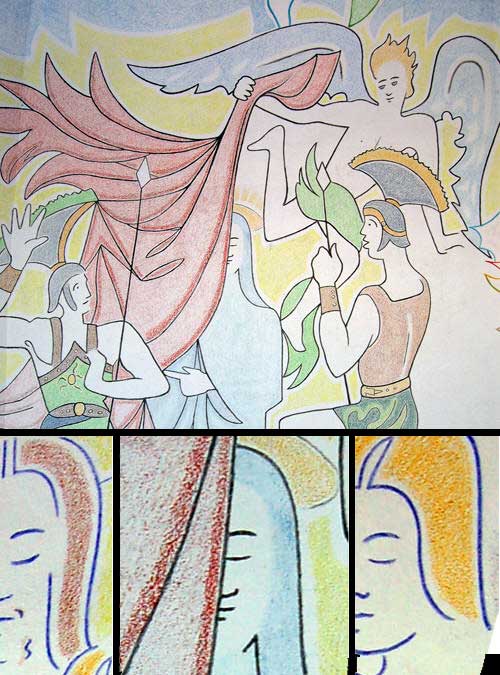

5. The Resurrection

Straight opposite the Last Supper, on the other side of the room there’s a mural of the Resurrection, this time clearly from the hand of the master himself. An Angel lifts the veil and uncovers a figure much to the suprise of the two Roman soldiers. It’s a strange scene indeed. Again, there’s the inversed ‘J’ symbol. The most prominent mystery here is the identity of the figure behind the veil. It seems a woman rather than a man from the shape of the body. Closer inspection reveals that the figure has no beard. It’s not Jesus that is resurrected here. Actually the figure looks a lot more like the person from the Last Supper identified as Mary Magdalene or maybe John. Perhaps there’s a clue in the outstretched hand of the left soldier displaying the ‘Five’ symbol again, the Last Supper taking place on a Thursday (the fifth day of the week in Jewish custom where Sunday was the first day).

Comparing faces, Left: Jesus at the Last Supper, Center: the figure in Resurrection

6. Angel of the Apocalypse

He is standing in front of an enormous orange sun. His chest is adorned with a cross. His wings spread out wide.

You can only wonder what he was meant to announce here in the strange combination of symbolism and religion.

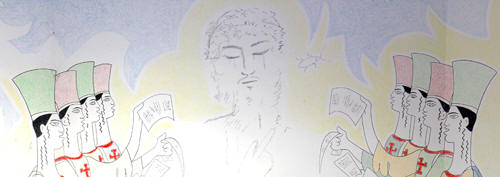

7. Adoration of Christ

Eight Jewish men read or sing to Jesus

Adoration of Christ is the title given to this work in a brochure in the Chapel. I am not so sure these eight men are adoring or chanting to Christ. They look like Jewish, judging by the curls hanging down from their heads. Looking at their faces you would think they are reading a verdict of some sort. On the other hand, since they all have their mouths open it’s more like they’re singing or scanting. They appear to be religious figures, perhaps the Sanhedrin. On their dresses they wear the Cross Potent. Their faces are serious and don’t look at Christ. The figure of Christ in the middle once again makes the ‘J’ gesture, at the same time pointing at a beetle crawling away from him. The depiction of Christ reminds of the Turin Shroud.

The beetle is an ancient Egyptian symbol. Inlcuding a scarab in the tomb was believed to ensure the rebirth of the deceased in the afterlife. This is quite significant. Wasn’t Jesus supposed to be reborn in this one?

8. Blason

Over the front entrance of the Chapel, a giant colorful Blason is painted in Cocteau’s hand. Two mirrored winged figures are painted around a shield with the Jerusalem Cross. At the bottom there’s a figure with an Egyptian looking headdress but he is wearing a necklace with a Christian cross. The black color and the facial expression indicate she is mourning. The whole thing is painted like some kind of blason or coat of arms. In the picture there are some symmetrical black and red dots. I tried to connect them but it hasn’t led to a distinguishable image so far. I am interested to hear if anyone can connect them up to reveal something meaningful.

Blason

Below the Blason, on both sides of the entrance, a figure, wearing a hat with the Jerusalem Cross, holds out his hands with the thumbs touching in the old Jewish symbol for divinity.

Cocteau, the Meticulous Director

Jean Cocteau firmly believed he would transcend time and space after his death, just like the man he shared the intials with: Jesus Christ. This re-birth would not take place in this life though.

It’s hard to tell exactly what Jean Cocteau had in mind when he designed the Chapel of Notre Dame de Jérusalem. When Jean Martinon asked him to design a Chapel for his Ideal City, Cocteau must have thought to create the Ideal Chapel. Sensitive as he was, he perhaps even had a premonition of death lurking round the corner, pushing him to make his last enigmatic work the most explicit of them all. A perfect symbiosis of shape and image. Did Cocteau hide something or the exact opposite? In either case, you can count on everything being there for a reason. You have to remember Jean Cocteau was a celebrated film director. He was known for meticulously detailing out his themes and messages. A micro-director, obsessed with the right word in the right line in the right poem. The right person in the right clothes in the right spot on the stage. Cocteau didn’t leave anything in his art to chance. He was very articulate. A symbolyst; certainly not an impressionist.

My guess is that the octagonal shape was meant to guard knowledge in this place for eternity. In a great double meaning of the same octagon it looks like that knowledge had everything to do with the alleged resurrection of Christ. The outer and the inner octagon.

Cocteau tells us Mary had sins and gave birth to the Infant Jesus through natural conception. He died on the cross and changed his earthly kingdom for a heavenly one. The artist appears to be telling Christ didnot return and won’t return at the Apocalypse. While the Crusader priests pray and chant, Christ sheds tears over them in heaven where he was just reborn as symbolised by the Scarab.

At the Last Supper all eyes are on Mary Magdalene. Remember Cocteau painted this in an age where everybody still believed she was nothing but a foul footnote in the bible. Cocteau emphasises her role even more in the resurrection, straight opposite the Last Supper. Not Christ but Mary Magdalene exits the tomb with a serene expression on her face. She knows he’s in heaven and won’t be back. It’s clear now who Our Lady of Jerusalem is: Mary Magdalene.

If this is what Cocteau meant to say, how does the Order of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre fit the picture? If the previous interpretation is correct, guarding Christ’s tomb would become a whole lot more relevant than it would be when he had walked out of it after his death. It would mean his mortal remains where laid to rest and perhaps still are somewhere today. In that respect the ‘J’ and inverted ‘J’ symbols are quite clear in their meaning: he, Jesus, is up there, not here.

Dieu le Veult, God wills it, however not as they thought he wanted it in the 10th century. Jean Cocteau, appears to show us the Crusaders went on a conquest for all the wrong reasons but found a Holy Sepulchre, worthy to protect through all times.

©2007-2012 renneslechateau.nl, all rights reserved

Additional credits:

Mairie et Office du Tourisme Fréjus

The Crusades, Robert Payne

Discussions on www.terugnaardebron.com internet forum

Original photos Corjan de Raaf

Panorama photo copyright Antonio Moya, many thanks!

This article was previously published on Andrew Gough’s Arcadia

et dire qu’il a fallu que je m'”exile” en Australie pour decouvrir ces bautes, ces verites et cette foi universelle. Mon sang Lorrain et mon ame de Templier n’ont fait qu’un tour… de manege enivrant et revelateur comme on dit chez nous: BLISS

Merci, et toutes mes amities

Eric Jean Claude Masson

Thanks! for this amazing article, which is simply define our religion , i had a assignment about Resurrection and i got a lot of help from your site.